The migration of the Western Orphean Warbler [(Curruca hortensis)] has long been an elusive subject in European ornithology. Few ringing recoveries exist, and the species’ Mediterranean focus means it has often been overlooked in broad-scale tracking projects that tend to prioritise more widespread songbirds. A new study published in the Journal of Ornithology finally changes that picture. Using multi-sensor loggers on six adults breeding in southern France, researchers have reconstructed a full annual cycle and revealed a migration strategy that challenges long-held assumptions about how small passerines negotiate North Africa.

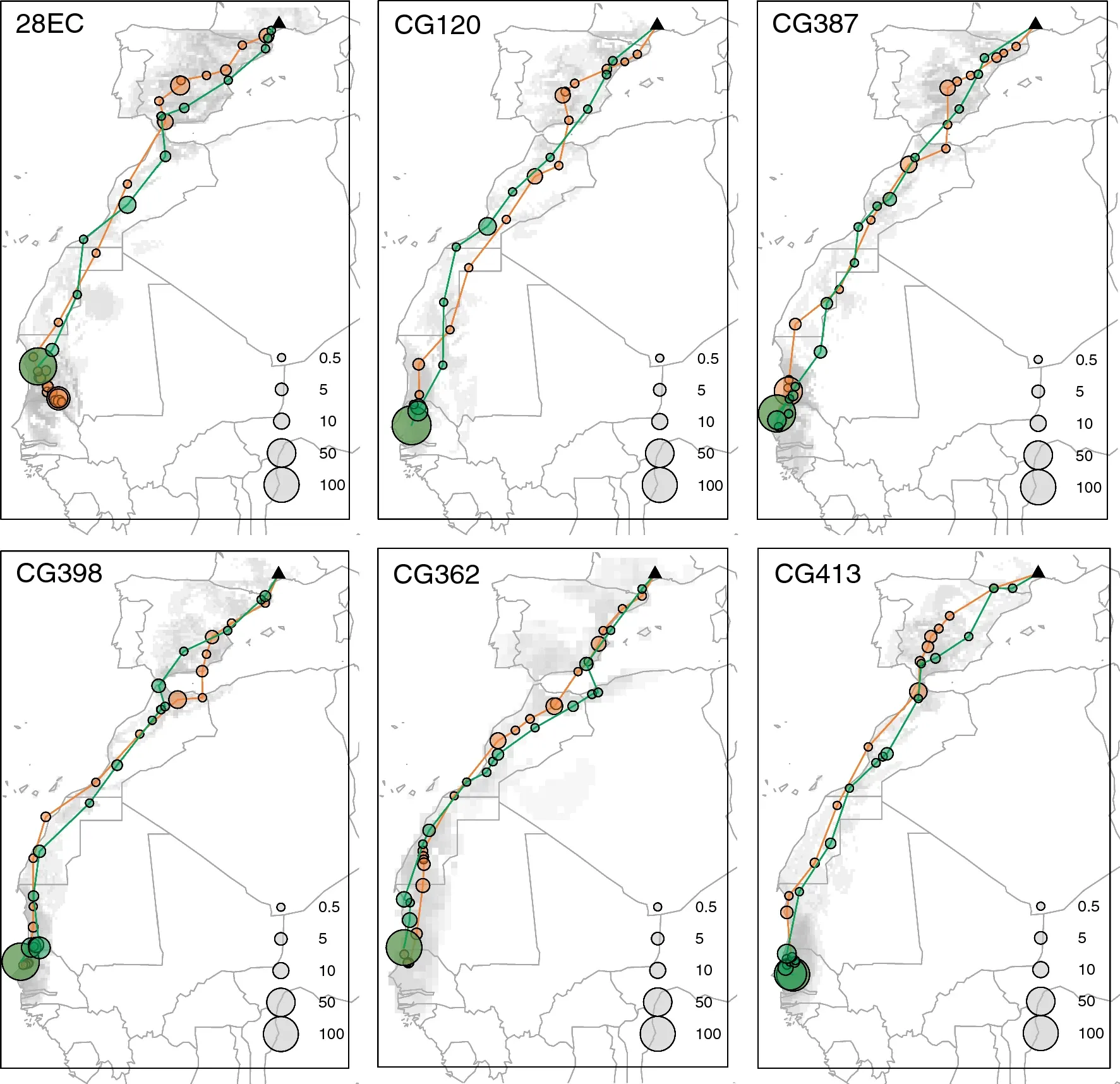

The birds do not plunge into the Sahara at all. Instead, they travel along the western desert margin, following a narrow corridor where the Atlantic’s influence softens the extremes and scattered acacias line dry riverbeds. Their routes from France to the Sahel, and back again, form remarkably straight lines, repeated with near-perfect consistency by every individual in both autumn and spring. For a species with such a small sample size, the uniformity is striking: each bird appears to follow the same inherited blueprint.

The tempo of movement is equally distinctive. Rather than performing long, uninterrupted flights of a thousand kilometres or more—as reed warblers, flycatchers and other trans-Saharan migrants routinely do—the Western Orphean Warbler progresses in measured nocturnal jumps of roughly six hours, covering about 300 kilometres at a time. These modest segments continue even across the desert edge. Stopovers are frequent, often lasting only a day or two, yet apparently sufficient for a species comfortable foraging in semi-arid habitats. The behaviour suggests not a bird attempting to outrun the Sahara, but one that has evolved to make use of every foothold along its boundary.

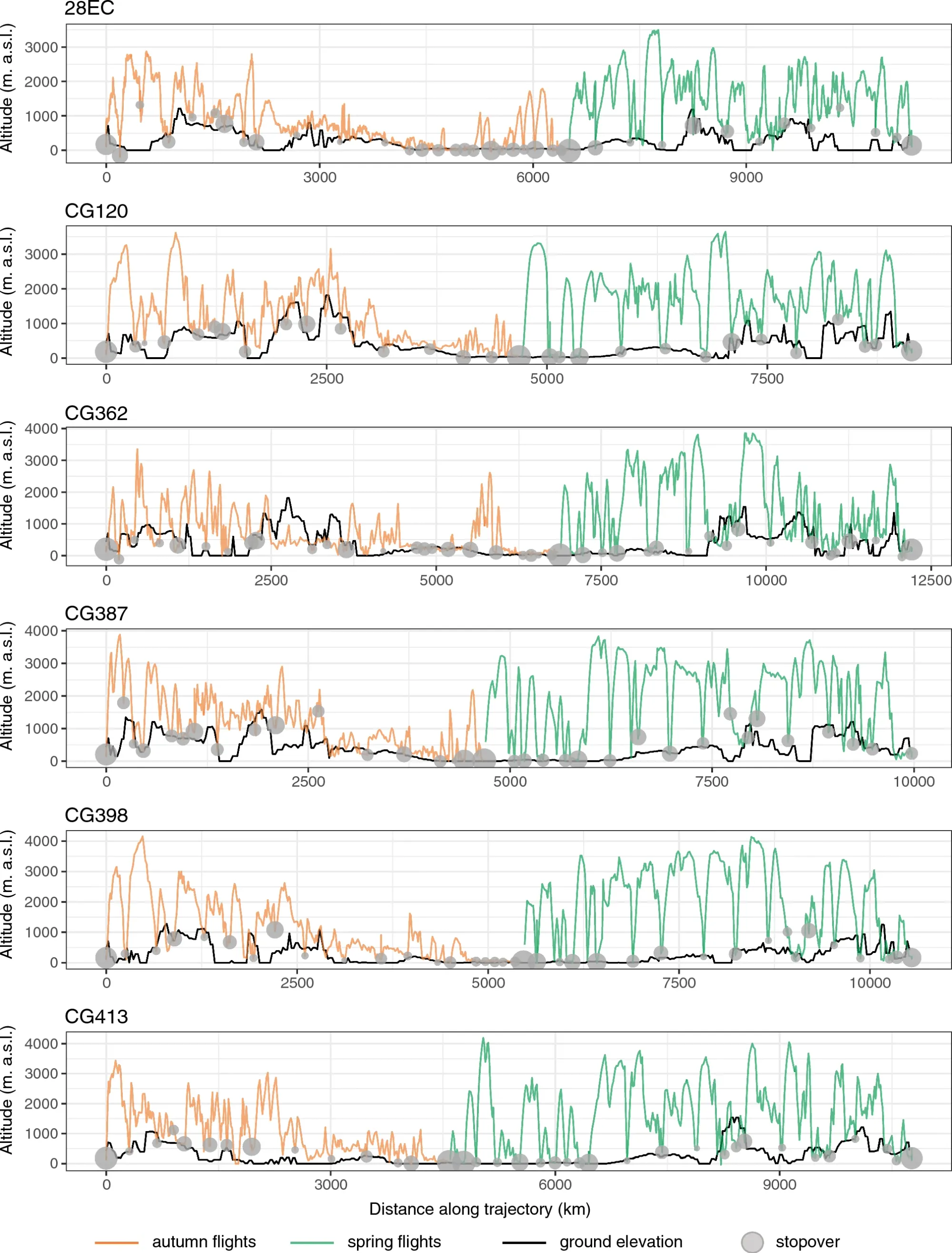

A clearer picture emerges when flight altitudes are considered. Autumn movements tend to remain relatively low, with long nocturnal flights averaging just above 1,000 metres. In spring, when the Sahara is far hotter, the birds climb much higher, reaching average altitudes above 2,400 metres and occasionally close to 4,000 metres. These vertical shifts bring the birds into cooler air and, potentially, more favourable winds. High-altitude spring flights appear to be less about speed and more about thermal management — an elegant solution for a species that migrates through warming skies on its return journey to Europe.

Another behaviour surfaced only through the use of multi-sensor devices. After dawn, when the birds descend rapidly from altitude, several individuals performed short, low-level flights that lasted up to an hour. The pressure readings showed they were already at ground level, yet the accelerometers indicated active wingbeats. These brief post-sunrise repositioning flights likely help the birds find suitable microhabitats — an acacia-lined wadi, a patch of shrubs — before committing to rest. They may also serve to correct for overnight wind drift. To detect such subtle behaviour would have been impossible with light-level geolocators alone; it required the combination of pressure, activity and light now offered by these new loggers.

Threaded together, these patterns reflect a species finely tuned to one of the world’s most complex ecological boundaries. A western route, favoured by oceanic moderation. A stepwise rhythm, relying on frequent short stops. A behavioural tolerance for dry landscapes that turns marginal habitats into functional stepping stones. And a consistent migratory corridor, shared almost identically across all individuals studied.

Understanding such details is more than descriptive. Climate projections for the Maghreb forecast substantial temperature increases, while the Sahel continues to lose trees under climate pressure and human exploitation. The Orphean Warbler’s migration depends on the persistence of sparse acacias and scattered vegetation along the desert’s edge. If these habitats decline further, the species’ carefully balanced small-jump strategy may face increasing constraints.

For now, the new findings illuminate one of Europe’s less-studied migrants with a clarity not previously possible. The Western Orphean Warbler does not cross the Sahara through endurance or sheer distance. It moves by precision, by timing, and by exploiting the thin, shifting line where ocean meets desert. In doing so, it reminds us that even the most understated journeys can reveal remarkable adaptations when viewed through finer scientific lenses.

References

Jiguet, F., Champagnon, J., Duriez, O., de Franceschi, C., Tillo, S. & Dufour, P. (2025). Crossing the Sahara by small jumps: the complete migration of the Western Orphean Warbler Curruca hortensis. Journal of Ornithology, 166: 737–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-025-02258-4